The System Wasn’t Built for This

Let’s start with the uncomfortable truth: the American healthcare system was not designed for chronic, progressive neurological diseases. It was built for acute problems — broken bones, infections, heart attacks. You go in, you get fixed, you leave.

Dementia doesn’t work that way. It’s a slow-motion crisis that unfolds over years, sometimes decades, involving multiple specialists, shifting care needs, byzantine insurance rules, and a web of services that nobody explains to you in advance. Working through it feels like being dropped into a foreign country without a map or a phrase book.

This article is that map. It won’t cover every scenario — your state, your insurance, your family’s situation will all create unique challenges. But it will give you the framework to understand the system, find the right people, and advocate effectively for your loved one.

Step One: Getting the Right Diagnosis

Many families spend months (or years) in limbo before getting a clear diagnosis. Part of this is the nature of the disease — early symptoms overlap with normal aging, depression, medication side effects, and a dozen other conditions. Part of it is a healthcare system that often dismisses cognitive complaints in older adults.

Where to Start

Primary care physician (PCP): This is usually the first stop. Your PCP can perform initial cognitive screenings (like the MMSE or MoCA test), order blood work to rule out reversible causes (thyroid problems, B12 deficiency, infections), and refer you to specialists. Be direct: “I’m concerned about memory changes. I’d like a cognitive evaluation.” Don’t accept “it’s just aging” without further investigation if your gut is telling you something is wrong.

If your PCP isn’t taking it seriously: Get a second opinion. You are your loved one’s advocate. It is okay to push. It is okay to insist. If you’re noticing changes that are affecting daily life, those changes deserve investigation.

The Specialists

Neurologist: A doctor specializing in diseases of the brain and nervous system. They can order advanced imaging (MRI, PET scans) and perform detailed neurological examinations. A neurologist is essential for distinguishing between types of dementia (Alzheimer’s, vascular, Lewy body, frontotemporal), which matters because treatment approaches differ.

Geriatrician: A doctor specializing in the health of older adults. Geriatricians are particularly skilled at managing the complex interplay of multiple conditions, medications, and functional needs that older adults with dementia often have. If your loved one has several health issues (heart disease, diabetes, arthritis) in addition to cognitive decline, a geriatrician can be invaluable.

Geriatric psychiatrist: Specializes in mental health issues in older adults, including depression, anxiety, psychosis, and behavioral symptoms of dementia. If your loved one is experiencing significant mood changes, hallucinations, or agitation, this is the specialist to see.

Neuropsychologist: Not a medical doctor but a psychologist trained in brain-behavior relationships. They perform comprehensive neuropsychological testing — a battery of standardized tests that takes several hours and provides a detailed map of cognitive strengths and weaknesses. This testing is often the most informative tool for diagnosing dementia type and severity.

What Tests to Expect

A thorough dementia evaluation typically includes:

- Cognitive screening tests — Brief tests like the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), or Mini-Cog. These take 10-15 minutes and test memory, attention, language, and spatial skills.

- Blood work — Complete blood count, metabolic panel, thyroid function, B12, folate. These rule out reversible causes of cognitive impairment.

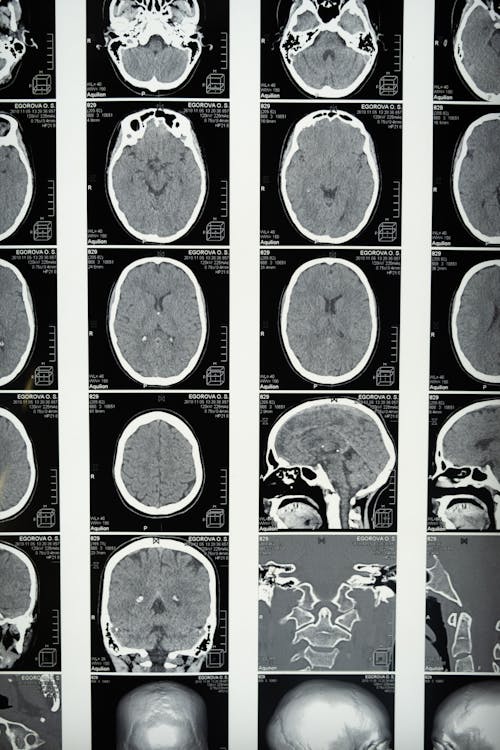

- Brain imaging — MRI is standard for assessing brain structure (looking for shrinkage, strokes, tumors). PET scans can detect amyloid plaques and tau tangles but are not always covered by insurance.

- Neuropsychological testing — If ordered, this is a comprehensive 2-4 hour assessment covering memory, executive function, language, visuospatial skills, attention, and processing speed. It establishes a baseline and helps identify the pattern of deficits.

- Blood biomarkers — Newer blood tests (like those measuring phosphorylated tau and amyloid ratios) are becoming increasingly available and can indicate Alzheimer’s pathology with reasonable accuracy. Ask your neurologist about these.

Understanding early warning signs of dementia can help you articulate your concerns clearly to the medical team.

Step Two: Building Your Care Team

Dementia care is not a one-doctor job. Over the course of the disease, you’ll likely interact with a surprisingly large number of professionals. Here’s who does what:

Medical Team

- PCP — Ongoing health management, medication oversight, referrals

- Neurologist/Geriatrician — Disease-specific management, medication adjustments

- Pharmacist — Medication interaction checks, dosing guidance. Don’t underestimate your pharmacist — they catch problems doctors miss

Support Team

- Social worker/Care manager — Your Area Agency on Aging (find yours at eldercare.acl.gov or call 1-800-677-1116) can connect you with a social worker who specializes in aging services. They know what’s available in your community and can help you access it.

- Occupational therapist (OT) — Helps adapt daily activities and the home environment to maintain independence as long as possible. An OT assessment of the home is incredibly valuable in early stages.

- Speech-language pathologist (SLP) — Can help with communication strategies and, later in the disease, with swallowing difficulties.

- Physical therapist (PT) — Maintains mobility, reduces fall risk, and can design exercise programs appropriate for the person’s abilities.

Legal and Financial

- Elder law attorney — Powers of attorney, advance directives, Medicaid planning, estate planning. National Elder Law Foundation (nelf.org) has a directory of certified attorneys.

- Financial planner — Specifically one experienced in long-term care planning. Certified Financial Planner (CFP) with elder care experience is ideal.

- Veterans benefits specialist — If your loved one is a veteran, VA benefits can significantly offset care costs. Contact your local VA or a Veterans Service Organization.

Step Three: Coordinating Care

The biggest challenge in dementia care isn’t finding specialists — it’s getting them to talk to each other. Each doctor sees one piece of the picture. Nobody sees the whole thing. Except you.

Practical Coordination Tips

- Create a master document containing: all diagnoses, all medications (with dosages and prescribing doctors), all allergies, all doctors and their contact information, insurance information, emergency contacts, and advance directive information. Bring copies to every appointment.

- Use a patient portal if available. Most health systems now have online portals where you can view test results, message doctors, and track appointments. If your loved one has given you healthcare power of attorney, you can be granted access to their portal.

- Request records transfers. When seeing a new specialist, request that records from other providers be sent in advance. Don’t assume this happens automatically — it usually doesn’t.

- Take notes at every appointment. Better yet, ask if you can record the visit on your phone (with the doctor’s permission). You won’t remember everything, especially during stressful appointments.

- Designate a care coordinator. In many families, one person becomes the central hub for all medical information and communication. If possible, make this explicit rather than letting it happen by default.

Step Four: Understanding Care Levels and When to Transition

Dementia care isn’t static. Needs change, and the care model has to change with them. Here’s the typical progression of care settings:

Independent Living (With Support)

For people in early stages who can manage most daily activities with some help — medication reminders, transportation, meal preparation assistance. In-home help (a few hours per day or week) can extend independent living significantly.

Assisted Living

When daily living tasks (bathing, dressing, medication management) consistently require help, assisted living provides 24-hour staff availability with a more home-like environment than a nursing facility. Many assisted living communities have dedicated memory care units with specialized staff and programming.

Memory Care

A specialized form of assisted living designed specifically for people with dementia. Features typically include secured environments (to prevent wandering), higher staff-to-resident ratios, dementia-trained staff, and structured daily programming. This is appropriate when safety concerns make standard assisted living insufficient.

Skilled Nursing Facility

For people requiring 24-hour medical supervision — complex medical needs, severe behavioral symptoms, complete dependence in all activities of daily living. This is the highest level of care outside a hospital.

Hospice Care

When dementia reaches its terminal phase, hospice provides comfort-focused care either at home or in a facility. Hospice is for people with a life expectancy of six months or less (though it can be renewed). We’ve covered this topic in depth in our guide on understanding hospice care for dementia.

Warning Signs It’s Time to Change Care Levels

- Falls becoming frequent despite home modifications

- Wandering or getting lost

- Unable to be safely left alone for any period

- Caregiver health is deteriorating under the strain

- Aggression or behavioral symptoms that are unsafe for home management

- Needs exceed what in-home care can provide (24/7 supervision)

The decision to transition care settings is one of the hardest a family will make. There is no perfect timing. Guilt is nearly universal. Give yourself grace — caregiver burnout is a medical reality, not a personal failure.

Step Five: Insurance and Financial Planning

This is where most families hit a wall. Dementia care is expensive, and what’s covered is confusing. Here’s a simplified overview:

Medicare

- Does cover: Doctor visits, diagnostic testing, some home health services (skilled nursing, PT, OT, SLP — but only if “medically necessary” and ordered by a doctor), hospice care, short-term skilled nursing facility stays (after a qualifying hospital stay)

- Does NOT cover: Long-term custodial care (help with bathing, dressing, eating), most assisted living costs, adult day care, 24-hour in-home care

- Medicare Advantage plans may offer some additional benefits (limited respite care, caregiver support) — check your specific plan

Medicaid

- Does cover: Long-term nursing facility care for those who qualify financially. Many states also have Medicaid waiver programs (Home and Community-Based Services waivers) that cover in-home care, adult day care, and some assisted living costs.

- Qualification: Medicaid is means-tested. Income and asset limits vary by state. An elder law attorney can help with Medicaid planning — there are legal strategies to protect assets while qualifying for coverage. Start this conversation early.

Long-Term Care Insurance

If your loved one has a long-term care policy, review it immediately. Key things to check: what triggers benefits (usually inability to perform 2 or more activities of daily living), daily benefit amount, benefit period (2 years? 5 years? Lifetime?), elimination period (how many days before benefits begin), and whether it covers home care, assisted living, and/or nursing facility care.

Veterans Benefits

The VA’s Aid and Attendance benefit provides additional monthly income (currently up to $2,431/month for veterans, $1,568/month for surviving spouses) to help pay for care. Eligibility requires wartime service and financial and medical need. Processing can take months, so apply early.

Other Resources

- Alzheimer’s Association — 24/7 helpline (1-800-272-3900) with trained staff who can help sort through care options and connect you with local resources

- National Council on Aging (BenefitsCheckUp.org) — Free tool that screens for benefits programs you may be eligible for

- State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP) — Free counseling on Medicare and insurance questions. Call 1-877-839-2675

A Final Word: Advocacy Is Your Most Important Job

The healthcare system is not set up to guide you through dementia care smoothly. There is no single point of contact. No one will call you and say “here’s what to do next.” You will have to push, ask, research, and advocate at every turn.

This is exhausting. It is unfair. And it is reality.

But you are not alone. Every resource listed in this article exists because millions of families have walked this path before you. They’ve fought for better coverage, built support networks, created organizations, and shared what they learned so the next family wouldn’t have to start from zero.

You are standing on the shoulders of a community that understands exactly what you’re going through. Lean on it.

Recommended Products

- Medical Organizer Binders for Caregivers — Keep all medical records, insurance documents, legal papers, and care notes organized in one place. A lifesaver for doctor appointments and emergencies.

- Elder Care Legal and Financial Planning Guides — Comprehensive books on dealing with Medicaid, Medicare, powers of attorney, and long-term care planning. Written for families, not lawyers.

- GPS Tracker Watches for Dementia — Wearable GPS trackers designed for people with dementia who may wander. Provides real-time location tracking and geofencing alerts for caregivers.

Affiliate Disclosure: This article contains Amazon affiliate links. If you purchase through these links, we may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. This helps support BrainHealthy.link so we can continue creating free resources for caregivers and families.